Select your region / language

Ian Devereux and the Story of Rocklabs

Now part of the global automation and robotics company Scott, Rocklabs began as an Auckland-based operation, but the story of what led founder Ian Devereux to build such a game changing company starts at the bottom of the South Island of New Zealand.

In 1956, Devereux, who was born and raised in Central Otago, finished high school, and decided to study a science degree at the University of Otago the following year:

“When I came to Otago University I didn’t know what I wanted to do but I had a general interest in science and took a science degree with a lot of different subjects. I thought I might end up in the agricultural world. I studied chemistry, physics, maths, geology and botany, thinking somewhere among those would be a career. I liked chemistry and geology and did a masters in chemistry, focusing on the geology department for my thesis.

I heard a lecture given by a scientist from the DSIR about the work going on at a place called the Institute of Nuclear Sciences, a geochemistry research laboratory in Lower Hutt. I went to work there in 1961 and in 1964 went to Auckland. Mind you, this was all to do with a woman who wanted me to come to Auckland! While I was working for the DSIR I studied for the PhD and the institute worked very closely with the university, so I was fortunate to be a full-time student at the university while I was a full-time scientist at the DSIR.

In Auckland there were tough times as people wouldn’t hire me because with the PhD, they said I was overqualified. I met up with Dr Jim Sprott, who was a forensic and industrial chemist. In 1969 we formed Rocklabs, specialising in geochemical analysis and fire assaying. Jim Sprott was involved in lots of things, most famously the Arthur Allan Thomas trials, after the Crewe murders. In those trials he provided evidence about the planting of a cartridge while I gave evidence about the wire that was used to tie the bodies. That was an interesting part of my career."

Rocklabs ran the laboratory but also began to sell more equipment. Equipment was sold to visitors from places like Australia and Canada, so the company began exporting instead of just selling in New Zealand. All this was unplanned, originally done as favours to customers, but just six years later, under the success of the exports it had had since 1970, Rocklabs began making sample preparation equipment on a commercial basis.

Laboratory work was not growing but there seemed to be a future in the equipment side of the business. There was not a market in New Zealand, where there was virtually no mining, but Ian Devereux was confident that having some real marketing work would bring success. His task was to convince the bank that there was a future in exporting. Faced with the proof of the orders from overseas, and that Rocklabs was the first company to be a specialist in this type of equipment, a $5,000 loan and a $5,000 overdraft was approved. Ian Gillies agreed to make the equipment and Ian Devereux undertook the selling. Three machines were made in the first batch. The plan was to sell ten machines in a year which would keep the business afloat.

By 1975 Rocklabs had orders approaching the maximum of twenty machines. The business was succeeding, in part because their competition was too slow. Customers could be waiting up to a year for a replacement machine from Rocklabs competitors, while Rocklabs kept a few machines in stock, as well as spare parts, ready to send.

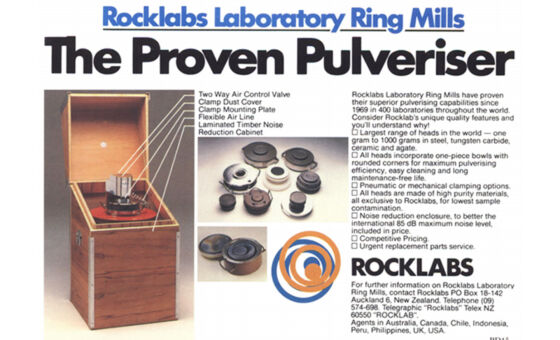

The Rocklabs range of Pulverisers in 1990.

“The pulverising machine was called a ring mill and consisted of a steel pot with concentric rings inside, and a lid. The crushed rock was put in the pot with the rings and the lid was put on. This was called a head which went on a machine that had a sort of hula hoop motion with an out of balance weight and this hula hooping motion set up all the rings inside which pulverised the rock. It was very fast and very noisy but would pulverise very uniformly and very finely. This machine, which was very new in our early days, has taken over almost every lab in the world for pulverising."

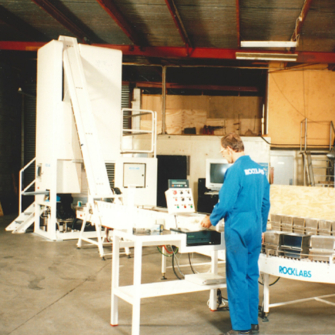

Rocklabs tried to keep things simpler than their competitors because the equipment was going into remote areas, such as 5,000 metres up the Andes in South America. Instead of robots, Rocklabs made mechanical devices, like small conveyor belts with a small bin containing a sample. A container would be packed with the components and then the system would be installed once the container reached the customer. The container could be taken into very rough country and orders were delivered to Russia, Canada, the United States, Chile and many other countries. Distance has not been a problem for Rocklabs but initially it made customers wary, as Ian Devereux recalls:

“Customers felt we were a long way away and they did not see New Zealand as a mining country. The distance was much more important to the customer when they thought of things breaking down, so we had to have a really good service. We’d get an order in the morning and within 24 hours it was on a plane. We built up a reputation around the world, people would say, “Gosh, you can get stuff to our mine faster than we could get it from the hardware shop down the road.” When we started off most of our competitors came from Germany and a few in the United States, but the latter just seemed to fade away, mostly due to environmental issues.

The lack of interest by the Germans was mainly from companies who made a whole range of products at that time. If you were starting up a mine you would go to one of these places and they could design you a whole mine, mainly coal mines, but they could do anything. From their perspective the lab equipment was very small and didn’t cost much and no one was really interested in it. The customer might wait a year and that was one of the reasons I thought we’d succeed because we were very small, specialised, flexible, and energetic. We’d be on a plane and off to see someone right away and so we were in an ideal position to take over a lot of this business.”

After a successful 30 plus years growing Rocklabs, Ian Devereux had begun thinking about retirement and wanted to sell the business to ensure it would continue to grow and be successful on the global stage. He was looking to sell to a New Zealand company when he came across a newspaper article stating that Scott were looking to acquire companies. The background was suitable – engineering, automation, and exporting. Scott Technology also wasn’t too big; Rocklabs had about 40 staff and Scott Technology about 160. The sale was soon accomplished.

Mining Industry

Learn more about Scott and Rocklabs products and systems for the mining industry.